There have been some great moments in Australian sport and others that reek of scandal, ineptitude and the downright bizarre. Here are four.

“Deportation, Mr. Djokovic”

Novak Djokovic couldn’t have picked a worse time to pack his bags, log onto Instagram and announce he’s heading to Melbourne. At the beginning of 2022, the city was so divided that the number of Covid cases was in the tens of thousands. Melbourne residents were so exhausted that a mass brawl broke out at a supermarket, with a shopper being hit over the head with a pot. Then Novak strolled in with his crazy vaccination ideas, his sloppy paperwork, his 20 Grand Slams and hundreds of millions in tennis earnings. He had no prayer.

The saga of medical exemptions, visa botches and entry permits dragged on and on. The grinning slogan “No-Vax” led the news every night. His supporters sang Balkan folk songs in front of his hotel. His visa application was a circus. Live streaming was characterized by long gaps, porn, spam and pirated content.

The Guardian’s Jonathan Liew noted that Novak treated the whole thing like a tennis match, “with an unshakable and messianic belief in his own supremacy.” He has contested his deportation as if it were a crucial turning point – as if it were his last stand against totality Oblivion.” The problems, Liew wrote, “arisen when you start to mix the hard, white lines of the tennis court with the messy compromises of the world at large.”

Essendon makes the push

According to Chip Le Grand in his book The Straight Dope, it was driven “by incompetence rather than malice.” That’s generous. The Essendon supplements scandal involved an election year prime minister, the country’s most powerful and defensive sporting body, mysterious new drugs, warnings of vulnerability to organized crime, an underfunded top anti-doping body, a haughty AFL boss and a rabid man Press, controversial sports scientists, senior bureaucrats, crack silks, human rights experts, golden boys, conspiracy theorists and flag wavers.

It was a perfect sporting shitstorm and the scandal needed a face. For months, James Hird’s ashen face appeared on the front and back pages. The AFL, as always, tried to control the narrative. Essendon countered with numbing press releases and lame hashtags. The natural inclination, whether you were a columnist, a tweeter, a keyboard hammer, or a water cooler bore, was to adopt as strident an attitude as possible. It won him several Walkley awards. It cost other Brownlow Medals. It has driven some crazy and driven others out of the sport. Few can explain with clarity what the hell actually happened. Essendon has never been the same since.

Fine cotton is left out

There had always been incidents at horse racing. In the 1970s, a gentleman named Rick Renzella – whom journalist Andrew Rule described as “a man of many qualities, most of them stolen” – staged a series of successful stings. The key, Renzella realized, was that the whiners had to vaguely resemble each other. But the ring-in between Fine Cotton and Bold Personality was a miserable mess. It was a group of experts, charlatans and weirdos, most of whom had no concern for intellectual concerns. First of all, Bold Personality was a full shade brighter and half an eighth of a mile faster than Fine Cotton. He also had a large white star on his forehead. Applying dye and peroxide didn’t help. A half-smart sixth grader could have devised a more effective scam.

after newsletter advertising

The fascinating thing about the Fine Cotton affair is that it was never fully explained or solved. While the Waterhouse family was not accused of being involved in the ring-in operation itself, it was discovered that they were already aware of the move. Bill Waterhouse, Rule wrote, was “a liar, a cheat and a tyrant.” When it was discovered that he and his son Robbie knew about the ring-in, they were “warned” by every racetrack in the world. But the racing world in Sydney was forgiving of all wrongdoings and Robbie eventually returned to bookmaking. Big Bill himself published a book “What are the Odds?” with a straight face, a nice turn of phrase and not an ounce of shame and took his truth to his grave in 2019. Robbie then married his wife Gai, whose horses won around the world, and his son Tom’s ads accounted for about 75% of all advertising on Australian television.

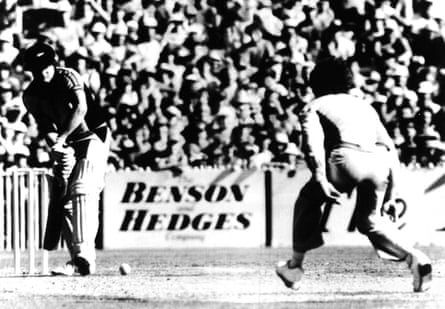

The forearm prolapse

The little girl tugged on Greg Chappell’s arm. “You cheated!” She cried. “You cheated!” On a terrible MCG pitch, he had scored 90 and bowled 10 overs in 41C heat. Now, with only one ball left in the limited overs clash against New Zealand, the series in order and the New Zealanders needing a six to force a replay, the Australian captain was sitting on his haunches in the middle of the game. The crowd – who adhered to the MCG’s two-plate maximum and lived in a pre-ozone world – had a lot of fun. But Chappell was in complete mental confusion. He longed for a day off. He later called his biography Fierce Focus. In that moment he was focused on two things – peace and the brick outhouse on the way to the crease.

Brian McKechnie was a Double All Black and represented New Zealand in rugby league and rugby union. As a batsman he was a good full-back. But he was a big boy. If anyone was ever going to hit a six, Chappell was convinced, it would be this guy. He asked his brother Trevor, “How can you bowl your armpits?”

You could only ask a younger brother something like that. Trevor wasn’t a world champion, but he was a good predator. McKechnie threw his bat in disgust and all hell broke loose. New Zealand’s prime minister called it “an act of true cowardice and I think it was appropriate for the Australian team to wear yellow.” In the changing shed, Mark Burgess threw his teacup against the wall – a typical Kiwi tantrum. Greg Chappell retreated to his hotel hideout, slept properly for the first time in months and was booed off to the SCG a few days later. He then received a standing ovation for his game-winning 87 points.